-

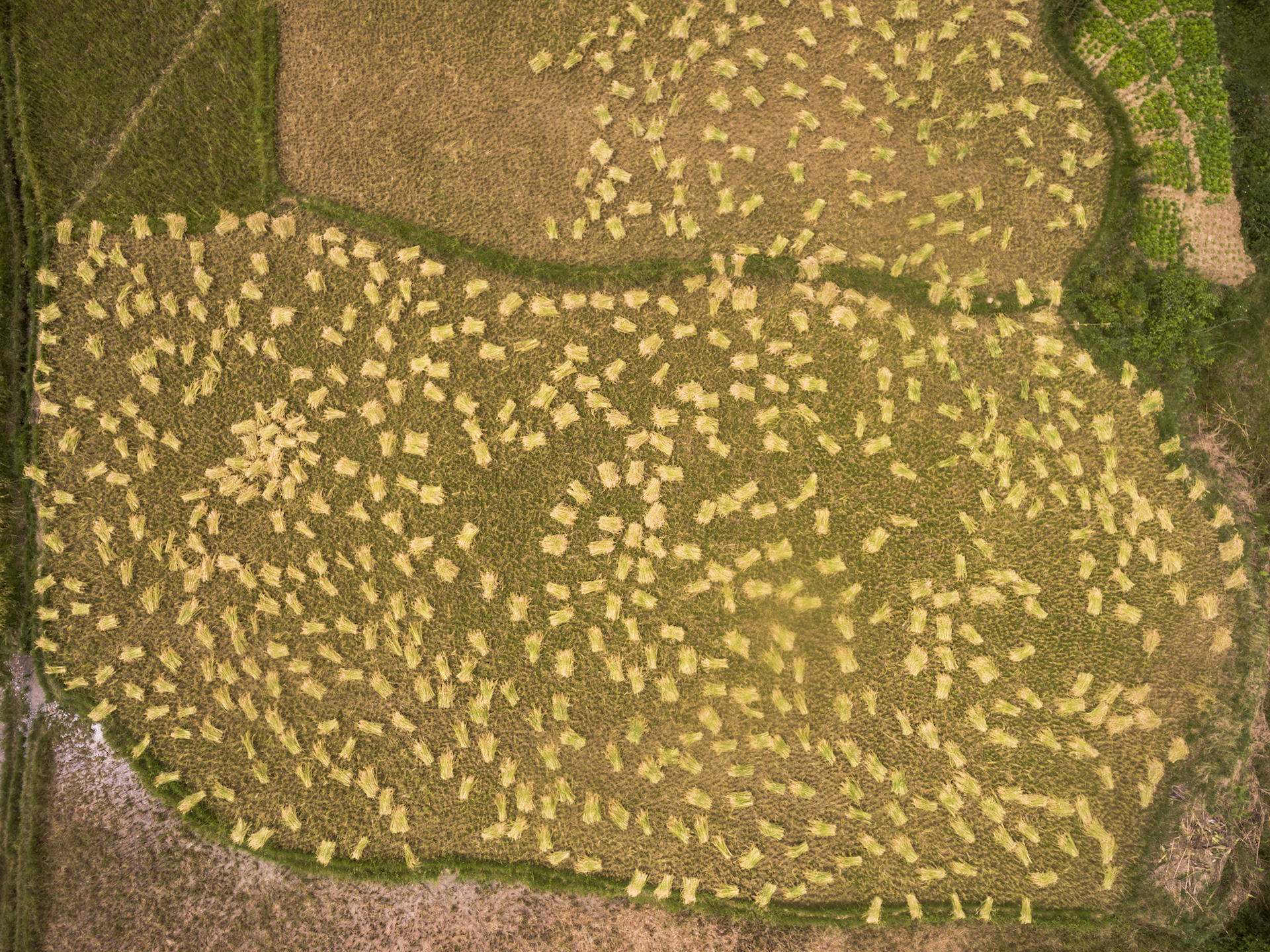

Sun falls on a rural valley in the highlands of Madagascar. Terraced fields of rice and maize capture the light to power the processes that enable the grains to fill and ripen.

-

Field by field and crop by crop, the time for harvest comes.

-

The Season of Rewards: Harvest in Southern Africa

Text by Paul Cox | Photos by Toby Smith

-

The rural countryside of Southern Africa provides two-thirds of the region’s people with a home and a livelihood, and provides nearly everyone with the food they eat. The crops that grow well in a particular country or province take on supreme importance in diets, cultures and daily life.

-

The people of Madagascar rank fifth in the world for per-capita rice consumption, eating an average of 136 kilograms per year. Zambians, meanwhile, lead the world in devotion to maize, eating 153 kilograms per year.

-

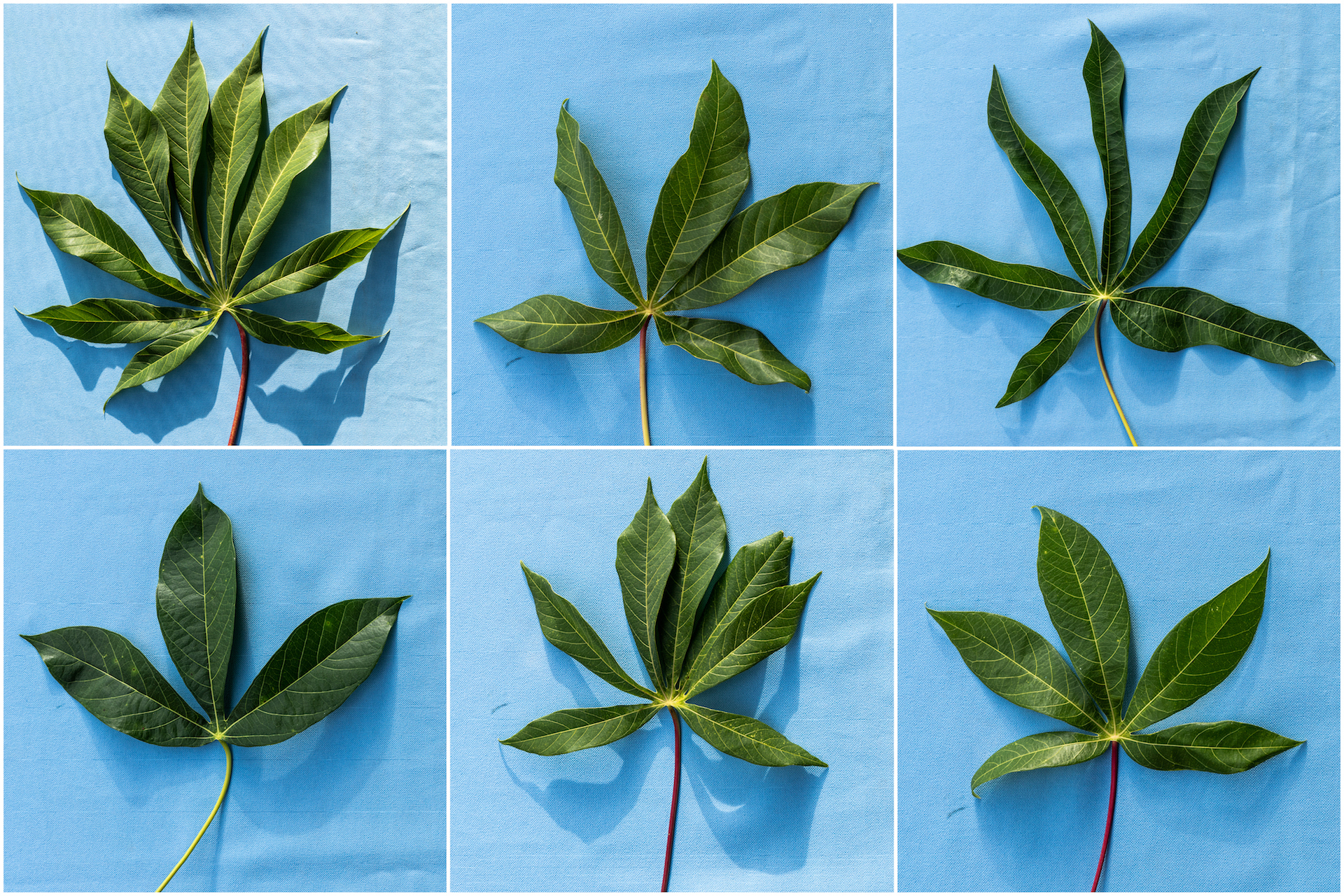

Compared with maize in mainland Southern Africa and rice in Madagascar, other crops, such as cassava, are less celebrated in the region. But for many people the cassava harvest is the most dependable and important of all.

-

Southern African farmers unearth 50 million tons of cassava roots every year, often from poor soils where maize and rice won’t survive. Cassava is the second most important food source, and since it doesn’t mind heat and endures droughts, it’s a rising star in a time of changing climates.

-

As part of its #CropsInColor collaboration with Getty Reportage, the Crop Trust sent photographer Toby Smith on assignment through Zambia and Madagascar to find maize, rice and cassava diversity in action. What he found was the harvest in full swing.

-

After a year of drought, farmers celebrated the season’s bounty as a personal triumph. They and their crops had overcome a multitude of challenges that are both hyper-local and profoundly global.

-

This story of harvest begins at the end: with food. In Zambia, the maize harvest is so fundamental to food security that the country has built an enormous system of reserves, which all purchase maize from many small farmers.

-

In some years Zambia exports maize to neighboring countries in the region, while in other years these reserves provide food to the country’s own people after drought disrupts a harvest.

-

Typically ground and cooked into a porridge called nshima in Zambia, the maize forms the basis for innumerable meals. In one survey of families, 99% ate maize nshima for lunch, 98% for dinner, and 78% for breakfast, too.

-

Maize came to Southern Africa in the 1700s. However, it didn’t make the journey from the New World just once. New diversity has been introduced regularly, and smallholder farmers embrace and adapt anything that works – especially if it works in the region’s dry and difficult environments.

-

Reportedly, some Zambian farmers are still growing a favorite variety called Hickory King that was introduced from the United States in 1905.

-

In recent years, an international partnership of breeders has successfully introduced another new type of maize: vitamin A-fortified orange maize. It looks striking in a country where white maize has always been favored, but its nutritional qualities, inherited from parent varieties found in the crop’s Latin American homeland, have made the orange kernels catch on.

-

It’s a welcome vitamin shot in a region where maize already accounts for 21% of the calorie supply and 27% of the protein supply, and where vitamin A deficiency causes widespread immune deficiency and impaired vision.

-

During the rice harvest in Madagascar, weekly markets spring up in every town. Farmers sell their extra rice and buy all of their household necessities.

-

They trade news of worries and weather. And they learn about new varieties – maybe taking home some rice seeds to try out next season. All over Southern Africa, the market is an important place where diversity and knowledge spread.

-

What doesn’t go to the market stays at home and goes on the plate. Happily, cassava can fill a plate all by itself. Milled or pounded cassava, like maize, is mixed with boiling water to make the porridge Zambians call nshima. While the roots provide carbohydrates, the plant’s plentiful leaves, pounded and cooked into a relish, are a source of protein, vitamins and iron.

-

Southern Africa is one of the few regions where the leaves are commonly eaten, but here they are considered a vital and delicious part of a complete diet.

-

In Madagascar, a visitor to a hotely along the highway will find most of the plates loaded with rice. Diners particularly enjoy pink or red rice in hearty soups eaten at breakfast. These special local varieties, which retain stripes of color from the bran after milling, are a Malagasy original and prized by farmers.

-

Other types are eaten with every meal, from a roadside snack to the elaborate feasts served during Santabary, a festival that celebrates the first rice harvest of the year.

-

The rice harvest in Madagascar is mostly a task for small farming families, with a little help from their neighbors. But on an island with 2.4 million farms, 85% of which grow rice, this small-scale agriculture adds up.

-

After several decades of recovery for rice production following a collapse in the 1970s and 1980s, Madagascar’s farmers are now back to producing more than 90% of the rice needed to meet the country’s formidable demand. This is a fortunate position, achieved thanks to thousands of years of experience and adaptation.

-

Other African countries – even some with suitable rice-growing conditions – pay heavy costs to import the grain. The import bill in the rest of Southern Africa is $725 million yearly, most of it incurred by South Africa.

-

As Southern Africa’s economies develop, new uses are opening up for old crops. Much of the cassava harvest is still peeled, soaked and pounded by hand, but technology for drying, milling and processing the roots into starch and flour is spreading.

-

In some countries, commercial beer breweries have begun adding this starch to their recipes. Elsewhere, entrepreneurs are experimenting with cassava chips as a source of ethanol biofuel.

-

New markets mean that more farmers are bringing cassava into their fields as a climate-smart crop, even in regions where it’s not well known as a food.

-

Whether there is rice to be milled, maize to be ground or cassava to be processed into starch, you often don’t have to look far in Southern Africa to find a shed, a machine and a mechanic.

-

All of these crops can be processed with hand power, but even a small engine-driven machine makes a big difference. A rice huller cuts out the labor of pounding rough rice to remove the hull, an inedible layer that surrounds each grain. Further milling removes the bran and germ to turn brown rice into quicker-cooking and more marketable (though less nutritious) white rice.

-

Good milling qualities – for example, rice grains that don’t break up inside the machine – are important traits that farmers look for in their crop varieties. In this way, crop diversity and processing technologies have developed side by side over time.

-

Not all machinery is small. Grain handling terminals and other large infrastructure announce the critical importance of maize in Southern African economies.

-

These towers are visible far across the plains, and at harvest the grain pours in from just as far, arriving from farms large and small. In most years, Southern Africa as a whole produces more of the crop than it consumes.

-

This big picture, however, conceals all kinds of local variations and problems. For urban residents, the most serious issues result from a combination of poverty and fluctuating prices.

In the capital of Zambia, Lusaka, a 2010 survey of households found that only 4% were food secure while 69% registered as severely food insecure. For these cash-poor families, the price of maize on the local market is among the most important facts of life.

-

Now empty of crops, with the harvest completed, pivot-irrigated fields in central Zambia will quickly be prepared for another planting. This could be maize, or another crop in rotation.

-

Half of Zambia’s maize production takes place on large commercial farms, which usually grow advanced hybrid varieties under irrigation. Seen from above their geometric patterns tell a story of precision and control. From this high up, it’s easy to imagine that diversity is less important in this mode of agriculture.

-

The truth is less visible: the sustainable production of these hybrids requires a constant effort by breeders to introduce new sources of resistance to pests, diseases and adverse conditions, and to keep yields high. In fact, farmers of advanced modern hybrids might need maize diversity more than anyone.

-

Harvests of every size depend on crops that are well adapted to their current environments and adaptable to future changes. Adaptation comes from diversity.

-

But where does diversity come from? Everywhere. For instance, cassava originated in South America, but now more cassava is grown in Africa than on all the other continents combined.

-

Unique diversity has been nurtured on African landscapes for centuries and collected in genebanks scattered around the continent. Most of these are field collections, tended and re-planted year upon year by dedicated staff.

-

The Southern African Development Community, with support from the Crop Trust, coordinates the region’s most important collections, which can freely exchange diversity with one another and with the global cassava collections based in Nigeria and Colombia.

-

The Southern African Development Community also maintains its own collective seed bank at the SADC Plant Genetic Resources Centre near Lusaka. Here, more than 17,000 seed samples are duplicated from national collections in Southern African countries, guaranteeing their long-term conservation and easy distribution to breeders.

-

This regional super-collection is a critical resource for food security in Southern Africa. Among many other crops, it holds 2,229 types of maize, collected from environments as different as the Congo Basin and the drylands of Namibia.

-

Madagascar’s national rice genebank in Mahitsy is another precious collection. Like the island’s lemurs, its native rice is found nowhere else on the planet. The crop landed more than 2,000 years ago after crossing the Indian Ocean from Southeast Asia, and farmers slowly selected the plants that suited their own needs.

-

Today Madagascar is considered a major secondary center of diversity of the Asian rice species, with special types such as pink rice that are widely different from existing Asian varieties.

-

The national collection has conserved more than 6,000 examples of this heritage since the 1980s. In 2010, the Crop Trust funded the regeneration of 2,421 seed samples that were in danger of expiring. In the process, genebank staff collected data on these landraces to help breeders make use of this national library of diversity.

-

Given Southern Africa’s fundamental reliance on agriculture, a crop disease or a drought has the potential to bring food security crashing down in a single sweep. But the region is hardly alone in this.

-

Even in the most advanced economies, diversity and security are tightly connected in the food system. Around the world, from basic economics to basic nutrition, everyone shares in the harvest, every day. This is why the world shares crop diversity: The problems and challenges can be very local, but the answers lie in a shared global resource.

-

Agriculture is different everywhere in the world, and always will be.

-

Farmers have their own crops, techniques and ideas, and they never stop innovating – because farming is always a preparation for the next harvest. Season by season, farm by farm, the result is an abiding strength in diversity. Sustained in fields and collections, the sum global total of this diversity is a harvest for all.