-

There is an ancient proverb that says, “When you lose your roof, you win the stars.”

-

Sometimes even amidst the gravest of circumstances, promise blooms. The International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), headquartered in Aleppo, Syria since 1975, was forced to abandon its genebank due to the ongoing Syrian war last October.

-

Today, ICARDA’s collection finds not one but two new homes in Morocco and Lebanon. The construction of the new genebanks is finalized at the same time that backup seeds, which came from the first-ever withdrawal from the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, are harvested in the fields and ready for cold storage in the new facilities.

-

Something Worth Fighting For: ICARDA’s Next Chapter

Text by Cierra Martin | Photo and Video by Shawn Landersz

-

Even before the war affected the city of Aleppo, ICARDA’s team sprang into action. They completed the duplication of over 85% of their collection in neighboring centers as well as in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

-

But by Spring of 2012, the situation in Syria began to deteriorate. With the realization that Aleppo would soon be affected, ICARDA’s senior management decided to decentralize their activities. In July of that same year, the international staff at ICARDA and their families were forced to leave the country to Lebanon, and with them went the remaining seeds that had yet to be safety duplicated.

-

Over the next three years, local Syrian employees with the help of nearby villagers would continue to send material out from the genebank in Aleppo to users around the world and succeeded in making the 6th and 7th shipment of seeds by ICARDA into the Svalbard Global Seed Vault – a dangerous exploit that would win the genebank’s team the prestigious Gregor Mendel Foundation award for outstanding service in the field of plant genetic resources.

-

Yet by 2015, sending out germplasm was becoming nearly impossible. While the seeds remained physically safe, the genebank couldn’t carry out its core activities nor fulfill its mission of sharing the material with users around the globe, “depriving the world from very valuable germplasm,” said Ahmed Amri, Head of Genetic Resources at ICARDA.

-

With this realization, they decided to relocate the genebank and re-establish their active collections not in one place but two. “What happened in Syria was a good eye opener for ICARDA,” said ICARDA’s Director General, Dr. Mahmoud Solh. “For 35-36 years, we’d put all of our eggs in one basket, therefore it was time that we really go out and decentralize our activities.”

-

The best locations to undertake these activities were at ICARDA’s existing research stations in Lebanon and in Morocco.

-

In Lebanon, ICARDA had its own experimental station in Terbol which has been active since the 1970’s, yet it wasn’t equipped with the cold rooms or the field equipment and laboratories needed to carry out the genebanks core activities. After ICARDA was forced to leave Syria, the American University of Beirut agreed to allow ICARDA to use their cold rooms at its farm in Bekaa until the new genebank facilities were up and running.

-

In Morocco, ICARDA again decided to utilize a research station generously loaned to them by the ‘Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique’ (INRA-Morocco) , where most of the ICARDA scientists and research teams involved in cereals and legumes improvement had been stationed. INRA provided cold rooms, offices and laboratories in Guich-Rabat, and ICARDA began plans for upgrading and rehabilitating the facilities in order to be able to host an international collection and carry out complete conservation activities.

-

The CGIAR, recognizing the importance of this work, funded and supported the upgrading and rehabilitation of the facilities in Morocco, as well as the construction of the new genebank in Lebanon.

-

Before the two collections could be rebuilt , however, ICARDA needed the seeds from their original collection. By the end of 2014, it was clear that moving the accessions out of Syria was not an option. After discussions with the Crop Trust, it was decided that the best way forward would be to utilize their backup seeds stored in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

-

ICARDA was one of the first users of the vault and had made seven deposits between 2009 and 2014, so the seeds were relatively fresh and all accessions of all crops had been duplicated there in one place.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault – Sowing the Seeds for the Future

-

One plane, two vans and 10,000 kilometers later, the shipments – made up of 128 boxes with over 38,000 seed samples – arrived at their new homes. A total of 57 boxes containing rangeland and forage species, faba beans, grass pea, and the wild relatives of cereals and pulses were safely received in Lebanon and 71 boxes containing accessions of cultivated wheat, barley, lentil and chickpea were delivered to Morocco.

-

There to greet these precious seeds were some of the staff from the original genebank in Aleppo and a few new faces too. Athanasios “Thanos,” Tsivelikas is one of the recent recruits and is taking responsibility for managing the collections in Morocco. Thanos oversaw all aspects of the Svalbard retrieval– from coordinating with the team at the Crop Trust in Bonn, to travelling to the vault in Svalbard, to sowing the seeds in the fields of Marchouch.

-

Thanos explained that there was a delicacy surrounding the entire process. Standing in the vault, looking at the boxes that made up the first ever retrieval from Svalbard, he felt an overwhelming responsibility for safeguarding this unique material for all of humanity.

And the feeling didn’t go away. After planting the accessions in the field, he and his colleagues knew that they had to get everything right. This was going to be the most important harvest that they had ever known.

-

Today – standing in a field brimming with thousands of healthy accessions, Thanos feels nothing but relief and happiness. “Here is the result of what we have achieved. As you see, the seeds were perfectly maintained in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault because everything has been germinating very, very nicely.”

-

The seeds retrieved from Svalbard were prepared for planting as soon as they arrived, and in the middle of October 2015 the first accessions were sown in the field.

-

4,000 of those accessions were made up of barley, a crop that originated in the Fertile Crescent around 8,000 b.c. Barley is one of the first known domesticated crops, and it was distinguished plant geneticist, H.V. Harlan’s work on barley in the 1930s that first sounded the alarm on crop diversity loss.

-

He writes, “The Egypt of the Pyramids, is probably recent in the history of barley. In the hinterlands of Asia, there were probably barley fields when man was young. The progenies of these fields with all their surviving variations constitute the world’s priceless reservoir of germplasm. It has waited through long centuries. Unfortunately, from the breeder’s standpoint, it is now being imperiled. When new barleys replace those grown by the farmers of Ethiopia or Tibet, the world will have lost something irreplaceable.”

-

Spaced 1.5 meters apart, each plot of barley, together with the thousands of other accessions conserved by ICARDA and other genebanks around the world, represents a remnant of agriculture’s beginning – a valuable resource for today – and a vital source of options for the future.

-

But the work in safeguarding these varieties is no easy task.

-

The first accessions of barley, as well as the other landraces of wheat, chickpea and lentil planted in Marchouch, reached maturity by May 2016, and the harvesting period began.

-

“The easiest way to harvest thousands of plots is by machine,” Amri explains. Yet, because preserving the genetic integrity of this material is so important, all accessions have to be carefully harvested by hand to avoid any mixture with neighboring accessions.

-

Following harvesting, a process called threshing occurs, where the seeds are separated from the chaff. The threshing machine is modified to suit the seeds of each crop.

-

After threshing, the seeds then have to be carefully cleaned from remaining chaff, soil, stones, weed seeds and broken seeds and placed by lots into the fumigation room, where they are fumigated to avoid any later damage from post-harvest insects.

-

Seeds are then transferred into the drying chamber where they remain for 4 to 6 weeks, gradually losing moisture content. Once dried, seeds are placed into air-tight containers to be kept in ICARDA’s cold room facilities for long-term storage. Pictured above: reference samples are taken for the herbarium.

-

29 September marked the inauguration of ICARDA’s new genebank in Lebanon which includes the cold rooms that will store these carefully prepared seeds. But Mariana Yazbek, ICARDA’s genebank manager in Lebanon, explains that “constructing a building with cold rooms is the easy part. For a well functioning genebank you need the genebank facilities, but also the field facilities.”

-

In Lebanon, for example, more than 14,000 accessions are growing this year alone, many of which are wild relatives, and they all require special conditions (isolation cages, plastic houses and more). “This number of accessions is more than the entire collection found in many genebanks,” says Yazbek.

-

In fact, ICARDA now holds the world’s largest collection of wild cereals, legumes and forages. These resources represent a “powerful weapon to fight climate change that threatens agricultural systems,” explains Amri. “Wild crops have robust properties – including heat, cold and drought tolerance, resistance to crop disease and pests – that can be bred into existing food plant varieties to make them more resilient and higher yielding.”

-

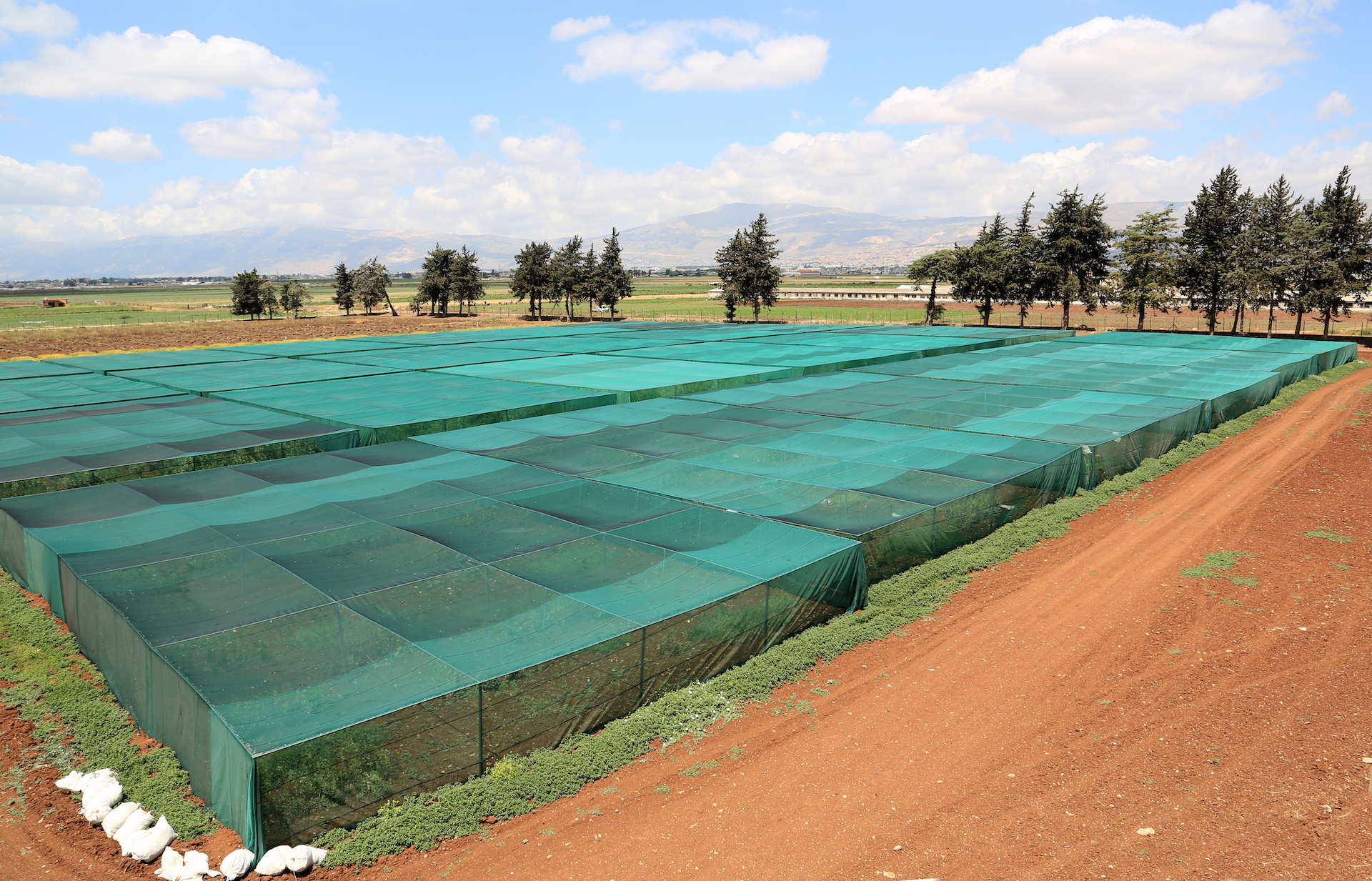

Lebanon is the center of diversity for many crop wild relatives, thus making it an ideal location to grow and conserve these wild species. Isolation in huge screenhouses or individual isolation cages are required for cross-pollinating species to ensure that the accessions remain true-to-type and are not diluted with pollen or seeds from outside.

-

The field work gets more laborious as the crops grow, explains Yazbeck, because these wild species “shatter” upon reaching maturity, meaning they drop their seeds on the ground. This requires staff to either bag the seed heads or literally pick up the dropped seeds.

-

After the material is harvested, there remains the process of cleaning, threshing and drying – as well as seed characterization and health testing before the seeds are finally put into storage. Conserving these species takes a lot of time and hard work but most importantly: a dedicated team of people.

-

Yazbek shares that after the move to Lebanon, ICARDA had to train and build an entirely new team. “Finding the people has been one of the biggest challenges” she says, “considering the very limited pool of people that are interested in this kind of hard work and have the dedication and commitment needed.”

-

But the people who do take on this work, take it on as a labor of love.

-

“There are two things that can bring happiness,” says Thanos, “either you make your hobby as a job or your job as a hobby. Working on plant genetic resources is far beyond a job for me. It is my hobby and at the same time a continuous excitement realizing the unlimited potential that these plant genetic resources possess for food security and sustainable agricultural development.”

-

It is the realization – of the unlimited potential contained within these crops – that keeps the dedicated staff at ICARDA as well as the other CGIAR international research centers and national and regional programs around the globe working so hard every single day.

-

Whether it be for resistance to pests and diseases, increased tolerance to extreme temperatures, resistance to more water or less water, crop diversity is a treasure that will allow us to combat climate change, improve farmer livelihoods and ensure food security. And in the face of adversity, civil war, typhoon, fire – this material is worth fighting for.

-

“Why it is so important has become known to everyone,” Yazbeck concludes, “but why I do it, joy.”