-

Mmm coffee. Its aroma rises and lingers in the air. You not only smell it, but see it too, in the swirling steam that sways upward and dissipates into nothingness. It teases you: come on, take a sip.

-

For coffee lovers everywhere, this might be a wake-up-early-morning brew, or a mid-morning mug. It could be an after-lunch pick-me-up, or an end-of-day wind-me-down. Whatever it is, you know that dark elixir will go down like nothing else.

-

And wherever you are, alone or in the company of friends or family, that rich, steamy drink is more than just a cup o’ Joe. It’s had a long history, wherein plants, people, culture, passion, science, technology and nature have played — and play — a crucial role.

-

MORE THAN JUST A

CUP O’ JOEA #CropsInColor essay on the role coffee plays in Central America

Text and photography by LM Salazar

-

Every day around the world, 1.4 billion cups of coffee are consumed. Take a moment and wrap your head around that number.

Try to imagine all those cups: 1,400,000,000 of them sitting on a never-ending tabletop.

Every. Single. Day.

-

And yet, still today – thousands of years after Kaldi, that mythic Ethiopian pastor, saw his caffeine-intoxicated goats frolicking around – not many outside the coffee world stop to think about what it really takes for us to enjoy our daily dose of caffeine. Do you?

-

I come from a coffee-producing country: El Salvador. My father owns a small coffee farm called Santa Isabel. But until recently, I’d never truly appreciated – or explored – that long cycle of production and transformation that starts in the fields and ends in a freshly brewed cup of coffee.

-

Moreover, I’d never really had the opportunity to spend time with those women and men who work in each of the steps that make up the whole cherry-to-cup production chain. That is, until recently.

-

Our latest #CropsInColor expedition took me to Central America, where I had the pleasure and honor of exploring the role coffee plays in that part of the world.

-

With logistical support from the Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center (CATIE) and World Coffee Research (WCR), I was able to dive head-first into a twelve-day, jam-packed exploratory trip through Costa Rica, Panama and El Salvador.

-

I visited 28 locations – from farms to mills to coffeeshops to research stations to cooperatives to diversity gardens, and beyond. Here is just a sample.

-

At Aquiares, a 129-year-old farm that sits high on the slopes of the Turrialba Volcano in Costa Rica, I walked into dense plantations during harvest season, awed by the swift, infallible hands that picked (strictly) the ripe cherries.

-

At the Starbucks Hacienda La Alsacia in Costa Rica, I tasted cherries picked straight off coffee trees, and savored their incredibly sweet and diverse tastes.

Welcomed by Carlos Mario Rodriguez, the company’s director of global agronomy, I walked through their coffee nursery, where, through selective breeding, Rodriguez is developing new varieties.

-

I did my best participating in tasting trials, which plantation owners, like Rachel and Daniel Peterson from Hacienda La Esmeralda, Panama, carry out every morning during their harvest season.

-

In El Manzano, El Salvador, sixth-generation plantation owner Emilio Lopez drove me in his four-wheeler up and down narrow dirt roads on what seemed like almost vertical slopes populated by perfect rows of coffee plants.

-

I walked through the maze of machinery that is the immense Volcafe mill in Heredia, Costa Rica, one of four plants in the country run by ED&F Man, one of the world’s largest traders in Arabica and Robusta coffees.

-

And, as daylight faded in Costa Rica’s Turrialba region, I spent time with Nicaraguan migrant pickers who live three to six months out of a year in a pickers’ camp that holds, during peak season, over 500 transient workers.

-

Other folks, indirectly, play a role here too — the coffee-centric tourism industry is alive and expanding. To the sound of a marimba playing “El Cafetal” (The Coffee Plantation) by Trio Los Panchos, I saw dozens of people from across the world visiting the DOKA plantation in Costa Rica, where they toured the 120-year-old wet mill.

-

At the San José gastronomy school O’Sullivan Culinary, Chef Oscar Castro treated me to a mouth-watering coffee-spiced meal: a mean T-bone steak bathed in Castro’s special coffee sauce, and a coffee tres leches dessert.

-

I also visited CATIE in Costa Rica, which houses a 70-year-old global coffee collection. Under the UN’s Plant Treaty, this is the only coffee diversity that is currently being shared across borders.

-

Here I saw wild coffees from Ethiopia and Sudan, among many others that, back in the 1990s, were used by CATIE, CIRAD (The French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development) and PROMECAFE (Programa Cooperativo Regional para el Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Modernización de la Caficultura Regional) in the development of hybrids, like the Centroamericano or the Milenio, which I later saw heavy with berries in several of the plantations I visited.

-

At WCR’s regional hub in Santa Ana, El Salvador, I saw new hybrids that are being evaluated for high cup quality and disease resistance.

-

These materials were also developed using the diversity found in CATIE’s collection. In fact, WCR safeguards a backup of CATIE’s core arabica collection here, which is also being evaluated.

-

Additionally, farmers like Esteban Sanchez in Costa Rica and Diego Llach in El Salvador, pictured here, are hands-on developing their own hybrids. Like them, it seems everyone is on the hunt for the next industry-changer.

-

Since 1779, the year Costa Rica started growing coffee, this crop has played a crucial role in all of Central America. During the nineteenth century, coffee helped transform these countries, ushering them into the industrial age – railways, train stations, roads and ports were built to facilitate exports of the “golden bean”.

In Costa Rica, coffee exports were taxed to help finance the construction of the National Theater.

-

From the 1850s to the 1950s, coffee was the largest agricultural export for these countries; an income generating commodity that altered the natural landscape, and in many ways defined their socio-political and economic realities. Unfortunately, for the local population, drinking quality coffee was next to impossible.

-

Historically, all the best coffees were exclusively exported, leaving the third-rate ones for national consumption.

And so, as Ricardo Azofeifa told me, “for years and years, the national clientele grew up on – and had been accustomed to – bitter, strong coffee. Add sugar, add milk, dilute and mask the coffee flavor, and try to enjoy it!”

-

But things have been changing. Azofeifa is one of the people leading the commercialization of high-quality local coffees for the Costa Rican market. Indeed, during the past few years, Central Americans have been rediscovering the endless, exciting tastes that coffee can offer us all.

-

Today, Central America has expanded far beyond its traditional role of simply producing enough coffee. In rural areas, many farmers are integrating vertically, expanding into the processing side of things. In Costa Rica alone, there are currently about 200 micro-mills.

-

And throughout the densely populated urban centers across the isthmus, independent coffeeshops as well as international and national chains are offering specialty coffees. Barista schools and educational programs are cropping up left and right, too, training a new generation of coffee connoisseurs.

-

In El Salvador, I met Alejandro Méndez, the first barista from a coffee-producing country to ever win the World Barista Championship. That was back in 2011, when he was 24 years old.

Today, Méndez co-owns two “4 Monkeys” coffeeshops and roasts national specialty coffees for an ever-growing list of exclusive clients.

-

In Costa Rica, I met Remy Molina, the 2018 New York Coffee Master, who works at the Specialty Coffee Association of Costa Rica (SCACR).

There, on the second day of my #CropsInColor trip, he prepared for me an exquisite cup of coffee using a Vandola, a 100% Costa Rican brewing device made of clay and inspired by Pre-Columbian art.

-

I drank so many amazing cups of coffee during those days. Most in the company of the owners of the farms I visited, like Antonio Barrantes Zuniga from Cafetalera Herbazu (Costa Rica), who told me that the market, both nationally and internationally, is changing.

Though more and more people appreciate and value a good cup of coffee, business is still precarious.

-

Climate change, and low prices well below the break-even point, among other things, are threatening the livelihoods of many of the 125 million people around the world that depend on this crop, and on this industry – from plantation owners to harvesters to mill workers who de-pulp, dry, select and pack the coffee, to exporters and wholesalers to roasters, coffeeshop owners and baristas, to the women and men conserving and exploring its diversity.

-

All of them are essential in the cherry-to-cup journey, as every step of the way must be carefully executed to assure the quality of the coffee that will eventually fill your cup.

-

Sadly, during my #CropsInColor expedition, I saw many abandoned farms. And some well-managed, productive ones hit hard by the fungus called coffee leaf rust (or simply roya in Spanish), the most destructive coffee pathogen in the world. Regions known for their coffee, like Tres Ríos in Costa Rica, are seeing more and more farms transformed into housing lots.

-

However, those stubborn and passionate coffee farmers that are in it for the long haul, those with the vision and means to alter their traditional way of doing things, have been developing niche specialty markets, catering to customers who are willing to pay premium prices for quality coffees.

-

At the heart of this transformation is the search for unique aroma and flavor profiles. ‘Cuppers’ talk about citrusy-flavored coffee, chocolate-flavored coffee, jasmine-like, bubble gum, vanilla-like, nutty, smoky – there’s a whole Flavor Wheel to help us describe our sensory experience.

-

And more and more people are exploring – or on the hunt for – unique and unusual coffees, as well as diversifying their production and processing methods.

-

Some are adopting more industrial approaches to farm management, taking cues from Brazilian producers.

-

Others, like brothers Martin and Edgar Ureña, owners of La Chumeca and El Pilón coffee farms in Costa Rica, are experimenting with aerobic and anaerobic fermentation methods.

These are but a few examples of the many ways that the region’s production and processing culture is changing.

-

Still, if we all want to drink that good old daily cup of comfort, we must understand that coffee diversity is the foundation of the entire cherry-to-cup value chain.

And beyond Arabica and Robusta, the varieties derived from just two species that are used in nearly all commercial production, there are 123 more species of wild coffee, mainly from Africa, that remain largely unexplored.

-

You can change the growing and processing, the roasting and packaging, the selling and the brewing method. But in the end, as CATIE’s William Solano told me, “it comes down to how we adapt this crop to new (and old) challenges.” And to adapt it, we simply must tap into its diversity.

-

But to tap into this diversity, we as a global community must make sure it is safeguarded and available, forever.

-

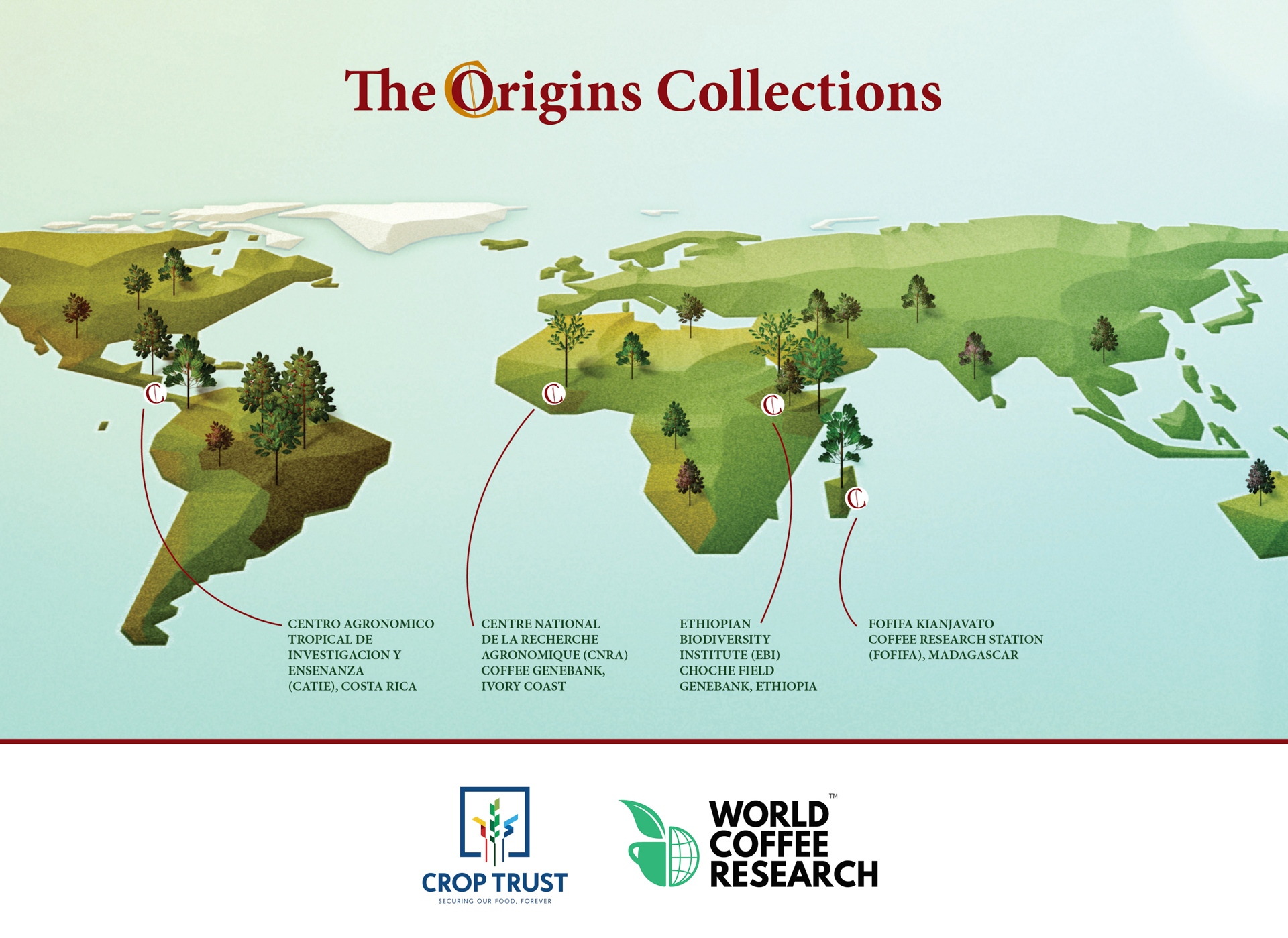

That is why, in collaboration with WCR, the Crop Trust carried out a global study in 2017 that identified where the largest diversity of coffee is being safeguarded. Building on this, we are working towards supporting these conservation efforts in the long term.

-

But we must act now, because this diversity is dying, in its natural African habitats, as well as in farmer fields across the globe, and even in genebanks. And because breeding resilient, knock-you-off-your-feet-tasting varieties takes time, and climate change waits for no one.

-

In the three countries I visited, production has been decreasing.

-

Abandoned farms – due to price or plague – mean less production. Farms converted into brick and mortar housing blocks mean less production too. They also mean fewer opportunities for those living in rural areas. And they mean less coffee, and less diverse coffee, in coffeeshops and supermarkets.

-

As I look back and take stock of what I saw and experienced during those twelve long and fruitful #CropsInColor days, I can firmly state that there is hope. Hope bred from hard work and passion. But also, and maybe more importantly, hope bred from the love of coffee.

-

Everywhere I went, I was welcomed by inspiring people – innovators and fighters like Ricardo Koyner from Kotowa Coffee in Panama. Though it is true that they may be a minority out there, these women and men are actively transforming the coffee sector.

-

We at the Crop Trust applaud their efforts, and with our #CropsInColor campaign celebrate their work.

-

Today, I invite you to join us in making sure all those involved in the coffee culture continue to thrive. Safeguarding coffee diversity forever is not a choice, but a vital, irrefutable necessity. Beyond it being the foundation of a multi-billion-dollar industry, it is – for millions across the globe – what gets us through the day.

-

So as you take that sip of your lovin’ cup, think about this: If Coffea diversity disappears, coffee as we know it will not be around much longer. And we’ll only have ourselves to blame.

-

#CropsInColor celebrates the critical importance of crop diversity and its beauty and cultural relevance across different landscapes. It highlights many key actors in our food systems – from consumer to farmer to seed bank – who are doing their part in safeguarding, making available and using crop diversity.

#CropsInColor is made possible by the generous support of Corteva Agriscience.

-

The Crop Trust and WCR estimate it will cost about USD 1 million a year to support the most important collections. An endowment fund of USD 25 million, paying out 4% per year, would provide that ongoing funding forever, without the need to scrape together funding year to year. The Crop Trust and WCR will now work to find funding for the Crop Trust Endowment Fund to ensure secure funding for the coffee collections, forever.

Invest today in the future of coffee. If 25 million people (out of the 7.5 billion worldwide) donated just a dollar, coffee would be safe forever.